December 2022

The Ages of Exploration are arguably one of the most crucial facets of modern civilization. Historians can come to sound conclusions on Western Civilization and its culture of discovery by probing these Ages separately and recognizing overarching themes pertaining to the cultural aspects of exploration. An understanding of Western Civilization itself is significant for scholars for it permits one to see the successes, shortcomings, and overall trends that have brought mankind to the modern period. This can be achieved by synthesizing analyses of several key aspects of each Age: their motivations and goals, their primary characteristics, and their arenas.

Aims and Motivations Throughout the Ages

One of the most defining aspects of the Ages of Exploration are their respective motivations and goals. Stephen Pyne, in The Great Ages of Discovery (The University of Arizona Press, 2021)discusses the idea that in the First Age, explorers were motivated by gold, glory, and God – “They wanted wealth, fame, and to serve the Cross.”[1]These motivational factors are witnessed in the many voyages that occurred in this age. Vasco da Gama traveled to Calicut for “Christians and spices”[2]; Columbus for gold and “a hereditary fiefdom…”[3]; and Bernal Diaz’s conquest of Mexico, for the notion of emulating “his ancestors that who had served the King, to advance the cause of the Cross.”[4] In three of the most vital voyages of the First Age, one can see the concise trend in motivation. However, one cannot fail to mention the essence of natural curiosity of man, for the idea of setting foot where no man has before tantalizes the explorative soul. God, gold, and glory certainly drove the explorers of this Age. However, the inherent motivation behind every voyage was a natural yearning for terra incognita. “A chivalric tradition and literature found new ways to express itself – new quests for knight errantry, new trials to endure and monsters to slay, new rewards, and in fact fabulous scenes as dazzling as any in romances.”[5] The notion of discovery for exploration’s sake is present throughout all three Ages, however, in the First, this sentiment was at its high point due to the lack of knowledge that society held about world.

The Second Age of Exploration carries differing motivations; though the aims remain similar yet evolved. Pyne states that “In the Second Age, intellectual culture, in the forms of an Enlightenment inspired by the example of modern science, and those other disciplines and arts influenced by the power of Reason, often led.”[6] The main inspiring factor throughout the Second Age was scientific advance and discovery, encouraged by the desire for the last pieces of terra incognita on the planet. The scientific facet can be inferred based on the logic behind the explorers of this age, primarily Alexander von Humboldt, who based his travels fully on the notion of scientific discoveries, all while planning to publish his studies and observations in a book – “At first he had planned on something like seventeen volumes to be published in six years, but he soon found that his project would have to be extended until it would finally reach thirty volumes, requiring a total of thirty years to complete.”[7] The scientific embodiment of the explorers in the Second Age also permeates through Captain Cook, although in the form of his assistant/navigator, Joseph Banks, who collected countless botanical specimens. Cook was scientific in the way that he circumnavigated and mapped many of the islands his voyage landed on and conducted a quasi-anthropologic study of the Indigenous at several landing spots. The fruits of this labor produced many peaceful encounters with the natives, though ironically, this also caused his death. The Second Age of Exploration’s motivations and aims can be loosely summarized by the concept of scientific and intellectual advance penetrating the culture of discovery, urged on by the preceding Age’s drive to fill in the map.

The Third Age’s motivational factors are the outcome of yet another evolution. Unlike the Second Age, yet more fierce than in the First Age, the ongoing Third Age of Exploration relies heavily on competition and technological advance as motivation. Repercussions of the Cold War are felt heavily in every aspect, by which “The United States and the USSR led the outpouring”[8]. The competition also occurred at the national level, seen in Ballard’s text, The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration (Princeton University Press, 2017), which holds a discussion of the differing companies pursuing to advance deep-sea research and technology. Science also continued to permeate through the layers of driving factors of the Third Age, however this transformed into sophisticated research using a variety of methods and technology not available to the Second Age. Pyne adds to this notion by stating that “Modernism had other ambitions [than the previous Ages of Exploration]. The hardware that made possible the Third Age had leaped beyond the cultural software to run it.”[9] Exploration, during the Third Age, evolved from the notion of Enlightenment reasoning, and turned “beyond what could be seen, felt, heard, or tasted”.[10] In essence, the Third Age has transcended the norm of empirical exploration.

Key Characteristics of the Ages

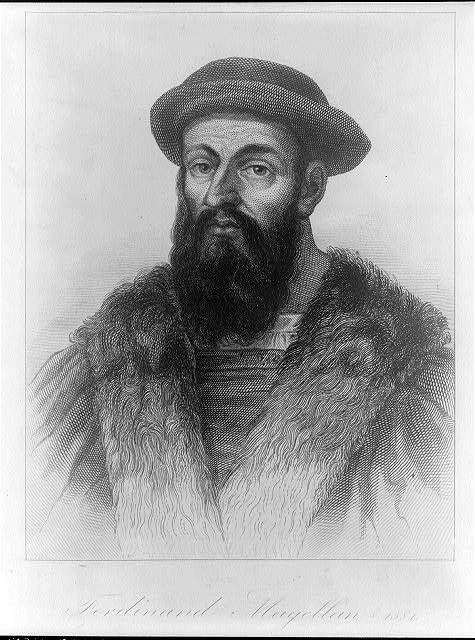

When analyzing the First Age of Exploration in relation to the other two, one can detect the beginning of a clear evolutionary line discerning their overarching characteristics. The Renaissance, occurring synchronously and running parallel in terms of culture, is a benchmark of the general persona of the First Age. Though effective in its aims to shorten the list of unknown lands, Pyne states that “the era of the Great Voyages [the First Age] was broad in its geography and brief in its history”[11]. The procedure used to shorten said list was almost brutish in comparison to the scientific sophistication of the Second Age, and the modernism of the Third Age; however, the explorers of the First Age did what they were able to do via the means that were available. This could be due to the simplicity of the “medieval mind”[12] that William Manchester of A World Lit Only By Fire (Little, Brown and Company. 2009) discusses at length. Anything that was new or displaced the norm was treated with a heavy skepticism, yet the most characterizing moment of the Age absolutely destroyed the normalized perception of the world. This defining moment, termed “medium aevum”[13] by Renaissance humanists, was the circumnavigation of the globe by Ferdinand Magellan. The upheaval in societal perception of the world seems to have set the standard of exploration, which then continued through the Third Age of Exploration. Like the Renaissance, Magellan’s voyage was a rebirth for discovery.

The defining characteristic of the Second Age of Exploration is the implementation of scientific research in discovery – this had several impacts on discovery and appears to stem from the void that was created by Magellan’s discoveries. He proved society wrong by realizing that the world is round, and that the ocean is one body of water, which seemingly would have left a large gap in society’s idea of how well they understood the world. The upheaval appears to have inspired more scientific study of the world, which the Second Age embodied not only in the oceans, islands, and unknown land, but also the interior of known continents. This notion is personified in the cataclysmic French Geodesic Mission to Ecuador, which Pyne claims is the birth of the Second Age. During this time, exploration took on a refined air, concerning itself more so with the inhabitants and features of unknown lands rather than the unknown lands themselves. Sophistication in this scope can be evidenced by the sheer number of scientific discoveries in the early fields of botany, anthropology, geology, biology, and climatology.

One can also argue that sophistication can be seen in the inter-European collusion that made the scientific facet both possible and popular – the scholarly Grand Tour of Europe. The tour, “universally applauded as a means to knowledge and stature”[14], took scholars to and from various European countries that held academic powerhouse institutions such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, meaning that scholars of all areas of study were able to gather to collude in research. In Alexander von Humboldt’s case, the Grand Tour enabled him to rub shoulders and pick the minds of figures such as Goethe, which made him well-prepared for his future voyages.

The key characteristics of the Third Age of Exploration are hyper-competition and a quicker feedback cycle. Competition constitutes much of the persona of this Age and is the main engine driving technological and explorative advance, however technology and its evolution play a key role. The rivalry between the United States and the USSR throughout the Cold War impacted the Third Age in a profound sense – exploration had evolved into a game of chess between world powers and was played in various arenas such as the ocean depths, the Poles, and in space. This greatly differs from the previous periods; however, it appears to be an evolution of the refinement birthed by the Second Age. In essence, the Third Age is to the Second what the Second Age was to the First. Third-Age exploration and development have furthered the sophistication of discovery to the point that it is entirely scientifically driven. The scale of this is both bigger and smaller than the previous Ages, meaning that the most minute advances in technology or science enabled exploration at a faster and more efficient rate – hence the quicker feedback cycle. This notion is embodied in the International Geophysical Year (IGY) from 1957 to 1958, which was cataclysmic for the birth of the Third Age due to the unity it brought to the scientific (and thus explorative) world through cooperation and competition. IGY has also brought forth cooperation amid competition by creating an international scientific community. This collusion has resulted in a much higher efficiency in development, allowing trial and error in the advancement of technology that the world has never seen before.

Arenas of Exploration

To fully understand each Age of Exploration, one must consider the arenas in which discovery took place. During the First Age, explorers carried out discovery via ocean travel to new lands, mostly islands. Discovery “assumed two forms”[15], with one form pertaining to the occurrence of proving that there was one world ocean and the resulting geographic discoveries. The other form concerns itself with the navigational tactics and methods used by explorers, which utilized predictable wind currents. “This meant ships could move from piloting to navigating, that they could let coasts recede from sight, take to the unmarked sea, and turn routes out into routes back.”[16] This allowed the explorers not only to take great voyages, but also lengthy ones. Thus, the First Age’s arenas lie on the ocean, its vast array of islands, and in navigation.

The Second Age concerned itself mostly with the notion of filling the map in where the First Age had left blank. Pyne states that “it sought out the last straits, sketched the last uncharted littorals, plotted the immense scatter of Pacific Islands, and discovered the final continents.”[17] Thus, the primary arena of the Second Age coincides with the First, however an addition of exploration of the interiors of continents arose. This is evidenced by the search for the source of the White Nile with various voyages throughout the interior of Africa, and the travels of Alexander von Humboldt throughout the interior of South America. These interior travels made most of the hefty additions to the world of science in this Age, for it appears that technology at the time was not yet suited for oceanographic research.

The arenas of the Third Age involve the depths of the ocean, space, and the Poles. These diverge greatly from the other Ages, though the ocean depths, or abyss, appear to be an extension of the past Ages’ arena of the ocean’s surface. Despite the shared realm of the ocean, however, the arena of the abyss employs tactics and methods that are completely new to exploration. It is important to remember that the ocean has been the common realm of exploration since mankind was able to build boats, therefore its surface has been explored more than any other arena. However, Ballard claims that until modern times, “it was impossible to study the deep ocean directly.”[18] Once exploration had advanced to the level that was necessary for it to turn its eyes to the depths, researchers were able to discover just how vast and complex the abyss can be. In fact, it is so vast that the ocean’s depths constitute “the other 97 percent of the earth’s biosphere”.[19] For these reasons, the abyss is considered to be “the most complex”[20] of all Third-Age arenas.

The other arenas of the Third Age involve the Poles and space. The Poles, or arena of ice, constituted many challenges for explorers until the dawn of the Mechanical Age of Arctic exploration, which commenced after the polar flight of Richard Byrd in 1929[21]. This led to the competition of the Cold War to reach the arena of ice and segued into the United States’ Operation Deep Freeze and the eventual Antarctic Treaty. As for the arena of space, the main driving factor constituting explorative motivation was the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union known as the Space Race. Space exploration poses quite the unique persona – it nearly embodies the sort of exploration that occurred throughout the First Age of Exploration in its brutish, wandering manner. This appears to be due to the unknown nature of space, and the early days of space exploration involved a large amount of full-sends into the darkness of the unknown. The arenas of exploration throughout all Ages of Exploration give deep levels of context for the reasonings, processes, and goals of not only the countries that took part in them, but Western Civilization as a whole.

Western Civilization

Through extensive analysis of the Ages of Exploration, one can draw a few conclusions about the explorative culture of Western Civilization. Primarily, either competition or cooperation are vital aspects of what push Western Civilization to explore. Having the yearn for discovery, or “the right stuff”[22], simply is not enough to drive an entire cultural movement of exploration. According to the characteristics of each Age, international cooperation and competition are what spur the bureaucracy to either support or allow exploration. This is evidenced by the competition between Spain and Portugal of the First Age, the cooperation of scholars and nations in the Second Age, and both the competition stemming from the Cold War and the cooperation of the scientific community in the Third Age. This notion can be furthered to claim that if all three parts are in synchronous occurrence, Western Civilization will inevitably explore. Without these key ingredients, exploration would be solely based on curiosity, though playing a large role in the overarching drive, could never be sufficient alone.

The characteristics of the Ages discussed in this text can also be synthesized into a conclusion on the impact of technology and methods used throughout the Ages of Exploration. In the First Age, discovery was carried out with existing technology and means. This is seen in the methods utilized by explorers such as Columbus and da Gama, however they were primitive and oftentimes unreliable. During the transformation into the Second Age, the technology advanced modestly, however the means and methods the explorers used changed more. This was mainly seen in the mindset of the explorers of this Age, in which their dedication lied almost solely to academia and navigation. Over the course of the Third Age, it seems as if technology has become the driving factor. This idea can be visualized through the advance of rocket technology in Wolfe’s text, entitled The Right Stuff (Picador, 2020), and especially in Ballard’s discussion of the creation of deep-sea research vessels. One can draw the conclusion that the use of technology has certainly evolved throughout the Ages and can see that its use has grown to overtake the human aspect of discovery so much so, that scientists have become the explorers of the Third Age. This can be viewed as a near-linear progression that evolves synchronously with Western Civilization, as the implementation of technology on a world-wide societal scale has been increasing as time progresses.

The importance of the Ages of Exploration to not only Western Civilization but also the modern world is both apparent and necessary for many reasons. By analyzing each respective Age separately and synchronously, one can draw several conclusions about Western Civilization’s culture of exploration. As this discussion determines, competition and cooperation are paramount for the motivation to explore, evidenced by the occurrences of both actions throughout the Ages. Alongside this conclusion, one can also track the trend of technology, its use, and its evolution throughout the Ages and find that technological advancement is one of the key driving factors of the ability to explore. The western world in modernity is what it is, who it is, and why it is due to its long, complex history of discovery.

Bibliography

Ballard, Robert D. The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Cambou, Don. Antarctica- A Frozen History. YouTube. The History Channel, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SxXjN7WT90.

Horwitz, Tony. Blue Latitudes. New York, N.Y: Picador, 2003.

Lansing, Alfred. Endurance. New York: Basic Books, 2015

Manchester, William. A World Lit Only By Fire. New York: Little, Brown and Company. 2009.

Moorehead, Alan. The White Nile. London: Perennial, 2008.

Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. Tucson (Ariz.): The university of Arizona Press, 2021.

Terra, Helmut De. Humboldt: The Life and Times of Alexander Von Humboldt, 1769-1859. New York: Borzoi Books, 1955.

Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff. Picador, 2020.

[1] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 28.

[2] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 31.

[3] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 31.

[4] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 31.

[5] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 33.

[6] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 12.

[7] Terra, Helmut De. Humboldt: The Life and Times of Alexander Von Humboldt, 1769-1859. 215.

[8] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 220.

[9] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 254.

[10] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 256.

[11] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 39.

[12] Manchester, William. A World Lit Only By Fire. 52.

[13] Manchester, William. A World Lit Only By Fire. 291.

[14] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 138.

[15] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 37.

[16] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 40.

[17] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 129.

[18] Ballard, Robert D. The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. 5.

[19] Ballard, Robert D. The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. 4.

[20] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 250.

[21] Antarctica: A Frozen History

[22] Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff.