December 2022

The Third Age of Exploration is an ongoing phenomenon that is being analyzed by historians which involves new uses of technology and new arenas of discovery – the Ice, the Abyss, and Space. One can gain a sense of understanding about these new arenas, both separately and synchronously, through various authors such as Stephen J. Pyne, Alfred Lansing, Tom Wolfe, and Robert Ballard. This is largely important to the study of the Age of Exploration, for splitting the different Ages and their contents into their respective categories allows for one to fully witness the transformations that took place. By engaging the works below, one can visualize the true characteristics of the Third Age.

Stephen J. Pyne, in The Great Ages of Discovery, Book III (The University of Arizona Press, 2021.),kicks off his discussion of the Third Age of Exploration by giving extreme importance to the International Geophysical Year (IGY), which “ranged from July 1, 1957, to December 3, 1958.”[1] The IGY is deemed important to the Third Age for a multitude of reasons, however Pyne stresses mostly that it was a catalyst for the Third Age’s birth and that it united the global powers through competition. The IGY occurred during one of the most politically unstable times the world has seen, and it provided a chessboard for the United States, alongside NATO countries, and the Soviet Bloc to duel in space, the depths of the ocean, and the barren, icy landscape of the Poles. In the arena of Ice, Pyne mentions quite a few prominent explorers and expeditions, however the focus in this discussion seems to be on the modernization that the Third Age ushered in. For the realm of Space, the author discusses the Space Race and the Cold War’s impact. Interestingly, however, he mentions that “The real action – the revival of geographic discovery – came through the exploration of the solar system”[2], and not the race to the moon, followed by an explanation of the various explorative voyages made by NASA. Later in the text, the author devotes a few pages to a discussion of the Voyager’s travels, and the abundance of data and knowledge mankind has gained from it. As for the arena of the Abyss, or the ocean depths, Pyne outlines the history by discussing the various vessels and advances that occurred in this realm. He explains that “Of the three grand realms for Third-Age discovery, the oceans were the most complex, the most integrated with earth, and both the most familiar and the weirdest.”[3] Following the discussion of the different arenas in the Third Age, Pyne moves to the modernist aspects of exploration that the new Age brought into play. This impacted the Age’s many voyages, and most of them would not have been possible without the new tools that technology provided. The author finishes off the text with an explanation of the political governances of the new realms, and that we currently are still living through the Third Age of Exploration, though in a period of stagnancy, and that we have likely already seen the peak of the newest Age.

Alfred Lansing’s text, Endurance (Basic Books, 2015), tells the story of Ernest Shackleton’s second Antarctic voyage from 1916 to 1916. This voyage started from South Georgia Island’s eastern port, and the goal for the crew of twenty-two men was to cross the Antarctic continent via sledges and ship. Their vessel, the Endurance, eventually was trapped by ice floes in the Weddell Sea for a considerable time before it succumbed to the ice. After stripping the Endurance of its useful items, lifeboats, and timber, the crew then hitchhiked across ice floes to the open sea, where they transformed the lifeboats into barely seaworthy vessels in hopes of reaching a whaling station. In these twenty-two-foot lifeboats, they eventually made it to Elephant Island after a grueling voyage. Once there, the crew recuperated for a short time, then Shackleton ordered four of his men to accompany him in sailing to South Georgia Island to be rescued. Leaving the rest of the crew behind, the small group traveled over 900 miles through some of the most dangerous waters on Earth, the Drake Passage. After many close calls with death, the crews were rescued. Lansing utilizes an abundance of source material, including interviews with several members of the voyage and every diary that was kept by those on the voyage, and tells this story with utmost detail.

The arena of Ice was further discussed by the documentary entitled Antarctica: A Frozen History (The History Channel, 2016). It starts off by explaining the history of the continent – its formation, the early 19th century sealers that hunted its shores, and the beginnings of the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration. The documentary follows this up by giving detailed summaries of the various early 20th century expeditions, such as the Voyage of the Discovery, Shackleton’s Nimrod and Endurance Voyages, and the race for the pole between Roald Amonson and Robert Scott. The film also mentions pilot Richard Byrd, who flew over the North Pole, which ushered in the Mechanical Age, the follow up to the demise of the Heroic Age that Shackleton’s death brought. The Mechanical Age essentially opened up Antarctica to the Cold War’s exploitation, and the documentary explains the United States’ Operation Deep Freeze at full extent. After this, the documentary concludes with a discussion on the danger that the continent is facing due to global warming and pollution, giving the viewer an understanding of what is at stake if the world does not treat this issue seriously.

The Eternal Darkness (Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017), written by Robert Ballard, brings to the table an in-depth history of deep-sea exploration. Starting off by discussing Beebee and Barton’s work with their first bathysphere, Ballard details the innovations, transformations, and advancements that led to the modern practices of deep-sea research and exploration. Following the topic of the tethered bathysphere, Ballard discusses the importance of being able to roam at depth untethered and free, which Piccard’s bathyscaph certainly achieved and set the standard. The creation of and further advancements of the untethered bathyscaph and the competition of the Cold War eventually led to the development of manned submersibles such as ALVIN, in which the author himself conducted research. The second part of the text primarily focuses on the scientific research that the manned submersible ALVIN was finally able to conduct. The main groundbreaking advance that Ballard discusses at length is the confirmation of Alfred Wegener’s theory of Continental Drift, which was proven by the then-new ability to analyze the creation and dispersing of Earth’s crust underwater in the Midocean Ridge. Throughout this research, scientists, including the author, were also able to study underwater geothermic vents and the process of chemosynthesis that their surrounding fauna utilize to survive. Both advancements were made possible by not only the development of manned submersibles, but also advancements in mapping technology, sonar, GPS, and computer-oriented hardware. All these advances made large waves in the scientific community. The third, and final part of the book draws its attention to the necessity, or lack-thereof, for submersibles to be physically manned. Ballard was a part of the HUGO/JASON project, which allowed wireless control of and real-time communication with unmanned submersibles. Ballard ends his text by providing an extensively detailed Further Reading section, allowing readers to fully explore the topic of deep-sea exploration.

Into the Submarine Fairyland (The Marginalian, 2022), written by Maria Popova, is an excellent article that describes the marine art made by Else Bostelmann, which is dedicated to the bathysphere inventor William Beebe. The article gives a small amount of context to the history of deep-sea exploration; however, it mainly focuses on the aspect of photography. The author then tells the story of Bostelmann, focusing on expeditions such as in Bermuda, where Bostelmann “went on to create more than three hundred stunning plates of marine creatures, many of them previously unseen by human eyes.”[4] Popova provides several examples of the artist’s work and gives a great deal of imagery to the study of deep-sea exploration, especially what type of creatures that researchers encounter. Similar levels of context to this topic are provided by the 2012 CNN video entitled The Legacy of Underwater Explorer Jacques Cousteau, in which a brief discussion of Cousteau’s work in deep-sea exploration is provided. Calling the researcher an “inventive genius” for his work with the Agua-Lungs[5], the video discusses the work on the saucer-esque bathysphere and some various aspects of the explorer’s personal life. This video is brief and leaves much more to be desired in the discussion of this monumental explorer, though it suffices as a strong summary of Cousteau’s work.

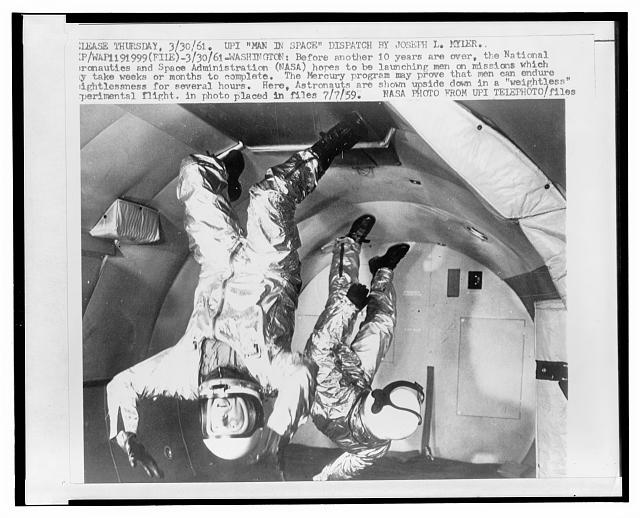

The Right Stuff (Picador, 2020), by Tom Wolfe, discusses the Mercury expeditions into space by NASA during the 1950’s and 1960’s. Wolfe starts his text by discussing that the fighter-pilot of the day either had the right stuff or simply didn’t, and this is what separated the best from the average; in the context of this text, it seems that this also defined the line between those worthy of being astronauts and those that are not. This notion is continuously stressed throughout the text, which gives fruitful context to the mental configuration of some of the pilots mentioned. Throughout Wolfe’s discussion of the right stuff, figures such as Chuck Yeager, his Mach records, and the rocket plane testing facilities that most of the Mercury pilots came from are discussed, giving context to the culture that surrounded the arena of Space. Following this, the text narrows its focus to the Mercury mission and its pilots/astronauts entirely, detailing the rigorous selection and training process, the nail-biting competition between NASA and the Soviet Union, and the many ups and downs of rocket testing. The author focuses the last half of the text with in-depth discussion on the Mercury missions themselves, keeping with the general trends of the book. Wolfe does an excellent job of getting into the mind of these pilots, though leaves much more to be desired in the discussion of the meta-aspects of space exploration.

Wernher von Braun’s explanation of NASA’s plan to take a trip around the moon and back in Trip Around the Moon (Walt Disney 1955) provides a unique perspective into the mindset of those involved with the arena of Space. This plan details an “advanced space base”[6] that would be able to refuel capsules, sustain life, and conduct research. von Braun then discusses the multi-stage rocket operation that would be necessary to get the prefabricated parts of the base into orbit. The proposition involves quite a bit of extreme precision, such as landing capsules into loading bays for unloading cargo. After showing how the base itself would be built piece by piece, von Braun concludes the video by discussing that this project would be very useful for testing models that would be utilized for adventures into deep space.

The documentary The Story of Europe Part 5: Commonalities and Divisions (Get.Factual, 2022) gives an extreme level of context to Europe’s political and social environment from the late 18th century to the mid-20th century. This film details specific events such as the conquest of Napoleon, the various French Revolutions, the Industrial Revolution, World War 2, and the formation of the European Union, all tied together to express the fragmentation that Europe had suffered from for hundreds of years, if not its entire history. In the next episode of the documentary, The Story of Europe Part 6: State of Play (Get.Factual, 2022), the focus shifts to how Europe has managed to combat the fragmentation in the forming of the European Union by stating “Europe has learned from its history; it’s put the battlefields behind it, and it’s formed its own union.”[7] On the other side of the matter, however, the narrator explains that nationalism and matters regarding immigration and refugees are impacting the unity that Europe is attempting to achieve, clearly seen in the 2016 occurrence of Britain opting to leave the European Union. Concluding the documentary, a firm stress is put on the dire need for Europe to somehow come together as one to combat the growing nationalist threats to the entire Union. Similar to The Story of Europe, the PowerPoint entitled Prof. Fernlund on Modernism Explores is a highly thorough overview of the Third Age of Exploration. The PowerPoint discusses various important aspects of the different arenas of this Age, which gives yet more context to the period. The material covers mostly everything that either Pyne or the other authors discuss, however in a different manner that allows for deeper understanding of the topics. One aspect of Dr. Fernlund’s text that was new, however, was a brief discussion of the G7 committee. This included historical background information that enabled the audience to understand the balance of powers on a global scale. The PowerPoint certainly piggybacks off nearly all the material for this module and gainfully builds off of important, yet under-discussed aspects to build a rich perception of the Third Age of Exploration.

The main reaction I have to all of these sources is a deep appreciation for global competition and cooperation. We see this cooperation in various aspects of Ballard’s text, in which different countries were working together to forge the technology that was needed to advance the exploration of our depths. The competition aspect is showcased by the Cold War, which drove the United States into a space frenzy. The competitive and cooperative qualities also play into the different arenas themselves – this is seen in Ballard’s and Pyne’s discussions of Piccard’s space invention paving the way for the first deep-sea vessels. It seems that the Cold War brought loads of scientific and explorative advance, not just in the mainstream ways that are well-known, but seemingly reaching nearly every aspect possible.

In terms of the materials themselves, I found all of them to be very enriching. Pyne, as per usual, provides the perfect amount of general knowledge about each aspect of the Third Age of Exploration, which leaves one yearning for more. This hunger is fed by engaging the other materials, where one can completely absorb themselves into a specific topic and come out of it with a good understanding. Lansing’s text mildly diverges from this model, as it felt more auxiliary to the film Antarctica: A Frozen History, which covered the general history of the icy continent. Lansing’s focus is purely on Shackleton’s expedition and certainly leaves more to be desired, though, with the apparent importance of that specific expedition, the deficiency can be understood.

Two of the texts, Lansing’s Endurance and Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, truly felt more like a novel than a historiographic book. This was not necessarily to their detriment; however, Lansing seems to have done a better job of molding the two genres together than Wolfe. Wolfe’s text reads and feels like an action novel and does not hold much onto the notion of space exploration by opting to focus more-so on the Mercury Program and the mindset of the pilots. The discussions about the mental aspects of these pilots surely gave insight to the why’s of space exploration in terms of the explorers themselves; however, it certainly left more to be desired, as I was looking for a more historiographic point of view and discussion about the arena of Space.

Each of the videos or documentaries did an excellent job of providing background context to each arena of the Third Age. This was extremely helpful in fully understanding the ins and outs of each arena’s aims, methods, and philosophy, which allows one to acquire a muti-dimensional understanding. Primarily, the Story of Europe episodes bring a different perspective than what I came to the discussion with, providing the Euro-centric point of view on the global matters and occurrences throughout the times. As an American, this is incredibly enriching and valuable because it allows me to analyze less as a curious American, but a curious human. On the other hand, I’ve wondered how Wolfe’s text would be different if I were not fully American. For the first time in exploration, the United States was a major leader, not one of the European explorative powerhouses, which certainly makes things interesting since the country is so young yet so mighty. This makes me wonder what the First and Second Ages would have been like if the United States had been discovered and colonized much earlier – would it have been a key contributor had the ability been present?

The Third Age of Exploration is certainly the fastest moving Age that the world has faced. By reading the works of the authors discussed in this text and engaging in similar scholarly materials, one can come to a full, multidimensional understanding of both the many key events that have taken place and their general trends. This understanding is extremely important to one’s perception of the world itself, for we as humans need to understand why the majority of the world is what it is, and why so – this, is the essence of humanity.

Bibliography

Ballard, Robert D. The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. Princeton ; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Cambou, Don. Antarctica- A Frozen History. YouTube. The History Channel, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SxXjN7WT90.

Disney, Von Braun A Trip Around the Moon. YouTube video, 1955.

Fernlund, Dr. Kevin. Prof. Fernlund on Modernism Explores. PowerPoint Presentation. 2022.

Lansing, Alfred. Endurance. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

The Legacy of Underwater Explorer Jacques Cousteau. YouTube. CNN, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCfwoNd2U6k.

Popova, Maria. Into the Submarine Fairyland: How Scientific Artist Else Bostelmann Invited the Terrestrial Imagination into the Wonder-World of the Deep Sea. The Marginalian, February 1, 2022. https://www.themarginalian.org/2022/01/14/else-bostelmann/.

Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. Tucson (Ariz.): The University of Arizona Press, 2021.

The Story of Europe: Commonalities and Rewards. YouTube. Get.Factual, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ZXIjd-uU_g&t=3044s.

The Story of Europe: State of Play. YouTube. Get.factual, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3mpZd0I0ek.

Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff. Picador, 2020.

[1] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 213.

[2] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 236.

[3] Pyne, Stephen Joseph. The Great Ages of Discovery: How Western Civilization Learned about a Wider World. 250.

[4] Popova, Maria. Into the Submarine Fairyland: How Scientific Artist Else Bostelmann Invited the Terrestrial Imagination into the Wonder-World of the Deep Sea.

[5] The Legacy of Underwater Explorer Jacques Cousteau. YouTube. CNN, 2012. 0:00:35.

[6] Disney, Von Braun A Trip Around the Moon. YouTube video, 1955. 0:1:00

[7] The Story of Europe: State of Play. YouTube. Get.factual, 2022. 0:14:20.